|

| |

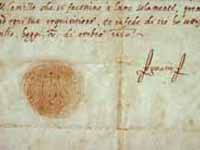

Overcoming and Ordering Dining with Saint Ignatius of Loyola: Rules for Regulating One’s Eating The book of the Spiritual Exercises includes a great variety of techniques and methods to help someone who is intent on drawing closer to God. As well as prayer forms, Ignatius includes more practical guidelines for daily living. Here Philip Shano looks at the contemporary relevance of one set of these, the ‘Rules for Regulating One’s Eating’. Download this article in PDF format by clicking here 'On You I Muse through the Night': The ‘Midnight Meditation’ in the Spiritual Exercise Anyone making the full Spiritual Exercises in their enclosed, month-long form may well be recommended to pray repeatedly in the middle of the night. Is this suggestion any more than a remnant of the late medieval piety with which Ignatius grew up? Paul Nicholson argues that, on the contrary, current science offers pointers to the benefits of such a practice. El Gran Capitán: An Influence on Ignatius and the Spiritual Exercises? It is widely recognised that, in composing the Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius drew on his own experience of prayer, but also of his life before his conversion. Tom Shufflebotham draws our attention to one possible significant influence, the ‘Gran Capitán’ Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, commander-in-chief of the armies of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella around the time of Ignatius’ birth. Ignatian Mysticism and Contemporary Culture If at one time Ignatius was viewed as the quintessential ‘soldier-saint’, he is currently more likely to be seen as one standing in the mystical tradition. Brian O’Leary recognises that this is in part due to an appreciation of certain ‘peak experiences’ he is known to have enjoyed in his prayer. But there is, he suggests, an ‘everyday mysticism’ discernible in the Ignatian story that is just as relevant for those who adopt his spirituality today. Reclaiming the Particular Examen Ignatius offers two forms of ‘examen’ near the beginning of the Exercises. The more general one invites retreatants to recognise more fully the presence of God in their daily lives. The other focuses on particular patterns of behaviour in order to modify them. Mark Argent here presents this ‘particular examen’ in the light of modern psychology. Theological Implications of the Ignatian ‘Contemplation to Attain Love’ as an Experience of Pentecost The Spiritual Exercises end with the ‘Contemplation to Attain Love’. Joseph Bracken believes that this prayer has the capacity to evoke in a retreatant an experience similar to that enjoyed by the first disciples on the day of Pentecost. Both experiences point to future mission, and offer the grace needed to carry this out. Third Things First: Preaching and Ignatian Contemplation Starting from the premise that today, in many parts of the Church, ‘explanation of the gospel has overshadowed experience of the gospel’, Geoff New finds in the Exercises a remedy for this situation. There is, he argues, no better way to ‘nurture and form a biblical and Christ-centred imagination’, and in this article he gives us a practical example. Ignatian Indifference and Today’s Spirituality The word ‘indifference’ can suggest either a cold, uncaring attitude towards a person, situation or question or the, perhaps hard-won, ability to stand back from our own immediate concerns in order to see with greater clarity. It is the latter that much of the Spiritual Exercises aims at attaining, but how is this standpoint to be best understood and appreciated? Robert Doud offers some answers here. From the Foreword I F ANYONE SHOULD ASK why Ignatius of Loyola compiled his compendium of spiritual exercises, he or she is clearly answered as soon as the preliminaries of the book that Ignatius produced are concluded. The Exercises are intended, according to paragraph 21, to help the person making them ‘to overcome oneself, and to order one’s life, without reaching a decision through some disordered affection’. This is certainly clear, but it is also likely to be off-putting to someone approaching the work today. The idea of introducing a little more order into one’s life might have its attractions, at least for those of a certain temperament. But taking a month ‘to overcome oneself’ sounds a great deal less enticing. It smacks of muscular Christianity, and an approach to God that many of us are likely to see as both outdated and unproductive.Yet the Spiritual Exercises as a book, and the making of them as a practice, have never been more popular. A number of responses to this seeming paradox are possible. It may be that the Exercises are given in a way today that meets intentions other than those Ignatius first envisaged, and so achieves ends that are more suited to contemporary life. Although this is a coherent answer, I do not think that it is a true one. Most who make the full Exercises are likely to believe, and believe rightly, that they are getting from them, broadly speaking, the kind of results that Ignatius intended. Is it perhaps, then, that retreatants believe the Exercises they make, like foul-tasting medicines, may be unpalatable but are somehow good for them? This response, too, does not fit my own experience, either as retreatant or as director, closely. For much of the month of the full Exercises the prayer periods are, if not exactly enjoyable, at least filled with the kind of consolation (to use the technical Ignatian word) that makes the praying of them welcome. Maybe the word ‘overcome’ lies at the root of the problem. It points to a reality that is often hard to face: the reality that there are things in my life that get in the way when I attempt to draw closer to God, or to allow God to draw closer to me. These are things that need to be overcome if the aim of the Exercises’ programme is to succeed. The crucial realisation is, however, that they are not overcome principally by my own efforts. It is, in the last instance, God who overcomes, and my part is to be open to God’s work, not to try and replace this work with my own. The articles in the current issue of The Way consider, from a range of viewpoints, how it is that the Spiritual Exercises work, how they achieve the ends for which they were intended. Mark Argent’s article analyses a frequently overlooked exercise that Ignatius offers those who are conscious of particular practices, outlooks or behaviours in their own lives that are inhibiting their spiritual progress. He shows how both contemporary psychology and Ignatius agree on a method of moving forward. Robert E. Doud helps us to see how indifference, in the sense in which the word is used in the Exercises, can likewise represent a freedom from attitudes blocking contact with God. Different parts of the Exercises contribute different things to the quest for God. Philip Shano offers a close reading of guidelines that Ignatius offers for regulating one’s eating, both within the retreat and after it, and shows how these might have a particular relevance to cultures such as those of the Western world today, where food and drink have become both plentiful and the subjects of fierce debate. My own article considers the practice of midnight prayer, mentioned frequently in the course of the month-long Exercises programme. Recent research suggests that this might have been less strange-sounding to Ignatius’ contemporaries than it is to us. At the same time, sleep science can offer clues as to how the process of internalising the word of God in this way works. Geoff New finds in Ignatius’ stress on the use of the imagination a powerful tool to move from explaining the gospel to experiencing it. The attempt to trace the source of the material in the Exercises, the question of where Ignatius got his ideas, is a perennially fascinating one. Clearly he drew on his own life experience, and Tom Shufflebotham portrays a military commander, known to Ignatius, as a probable inspiration. For Joseph Bracken, the experience of the first disciples of Jesus at Pentecost stands behind the prayer that concludes the Exercises, the Contemplation to Attain Love. Brian O’Leary, finally, points to Ignatius’ own experience of mystical prayer, of a kind deeply rooted in everyday life, as his ultimate touchstone. Paul Nicholson SJ Please click here to subscribe to The Way, | ||

| |

|